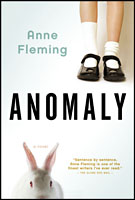

When Glynnis Riggs takes her albino sister, Carol, for show and tell in Grade Two, she sets off a chain of events that ends with Glynnis in hospital and their normally unflappable mother in crisis. For elderly Miss Balls, the accident is a happy one. Since her ousting from the Girl Guides, she’s been languishing, rehashing memories of nursing in World War I. Now she’s needed again.

Anomaly follows the four from 1972 to 1982, when Carol turns punk, Glynnis comes out, and Toronto comes of age.

Carol

When her mother dropped her off at the new school on the second day, Carol was surprised to find that it actually looked a lot like the old school, where they'd just left Glynnis. Three storeys high, deep red brick, with a sort of churchy, old-fashioned main door that probably nobody but parents and teachers used, and the very same head-high evergreen bushes on either side of the steps leading up to it.

READ MORENone of this had she noticed yesterday. Yesterday she'd been looking at her new Christmas mukluks and humming the mukluk song in her head to distract her throat from her stomach, which felt like it could upchuck any second. Her feet in her mukluks, on the other hand, felt perfect, all cushy and enclosed. The rest of her was hot and bulky inside her duffle coat, except for her legs, cool in their scratchy leotards. In the land of the pale blue snow, where it's ninety-nine below, and the hm-hm-hm hm-hm-hm hm-hm-hmmm, her head went as her mother pulled on her mitted hand. Her mukluks, sleek animals, nosed up steps, through a door, down a hall, up steps, through a door, then stopped. Her mother's hands appeared below her chin, tugging on the lapels of her coat. -A brand new start, Carol, just think of it. A brand new start. Chin up, now. The mukluks were sealskin. Not real sealskin, Jay said, but Carol liked to think of them as real seals.

Adult shoes stepped into her circle of vision, lady adult shoes. Adult conversation occupied the air above her.

-What did I say, Carol? Chin up. You can't live your life looking at your shoes. Low quarter-chuckles, more adult exchange. Carol lifted her head but kept her eyes on the boots. Puddles were forming beneath them from the snow. If they really were seals, they'd just go diving away in the sea, and she'd go with them to the land of the pale blue snow. A brand new start.

-Carol? Remember Miss Boskovich? Remember we met her before Christmas? -It's Mizz Boskovich, the other voice said, - but never mind.

Glynnis

She had been planning, for show and tell at school that day, to take the Beefeater doll her mother had brought back from England that summer, to talk about the Beefeaters and the Tower of London, and executions and the princes in the tower. But last evening, Camper Barbie had knocked the Beefeater's head off playing kung fu fighting.

It had been a glitch, headlessness, but it seemed to be a rectifiable one. All she needed was a paper clip to fish out the elastic inside the body and snap it over the hook that stuck out of the lower end of the head.

-Glynn-is! Her mother called her to set the table.

She rummaged in the drawers of the desk she shared with Carol. Carol's drawers were neat and tidy, which made it easy to see there were no paper clips. Glynnis' drawer was crammed to the top.

-I'm not asking you again, called her mother.

-I'm coming, Glynnis yelled.

Glynnis turned the drawer over on her bed and spread out the contents like Hallowe'en candy. So many things she'd forgotten she had. A broken watch found in the park. One Labatt's IPA beer cap amid a whole box of Blue and Export caps. A set of Snoopy pencils. A crochet hook? She didn't know where it came from, but it would certainly do the trick.

Carol marched into the room. She had two walks-a bobbing, long-strided one when she was happy or she felt in charge, and a slouching shuffle when she felt sad or put-upon. Today it was the bob. -Mom says if you're not downstairs in less than a minute, your tv privileges are suspended for a week. She turned smartly on her heel and bobbed two steps, swinging her arms, before bobbing right onto the Beefeater's head, smashing it into plastic shards.

Carol. 'Clumsy Carol,' as their father had taken to calling her lately. (Glynnis was 'Glamorous Glennis,' after the plane Chuck Yeager flew to break the sound barrier.) That week Carol had already broken a good china teacup, a lamp, and the towel rack in the bathroom. Now it was the Beefeater's head.

-I'm telling, Glynnis said.

-Go ahead. It's your fault for leaving it on the floor.

-Fine. Glynnis started for the door. -Mom! She pitched her voice loud enough to sound like she meant it, but not loud enough for her mother to hear.

Carol caved in. -Don't! Please, Glynn? Pretty please? I'll... I'll... give you my allowance.

At dinner, Mrs. Riggs asked if Glynnis was ready for show and tell.

-Of course, Glynnis said. She was annoyed at the tone in her mother's voice that implied she expected her not to be, and at the look that followed, implying she did not believe her when she said she was. Glynnis didn't have to rehearse everything the way Carol did. If she knew what she was talking about, she could make it up on the spot, which she did now.

-This is a Beefeater doll, Glynnis held up the imaginary doll. -The Beefeaters were guards at the Tower of London that was a prison. They're called Beefeaters because they ate beef when not everybody had enough money to eat it. The Tower of London is where Henry the Eighth's wives were kept before they were beheaded, about which there is a song that goes, ‘With 'er 'ead tucked underneath 'er arm she walked the bloody Tower.' It's also where the Princes in the Tower were kept, who were heirs to the throne, but they were put there by Richard the Third who was their uncle and who people think killed them.

-Well! her mother said, beaming, -I am impressed.

There was not much to be impressed about, but Glynnis accepted the praise anyway. History was her brother's hobby, British history in particular. He could recite kings and queens for days. When they were younger they'd pretended he was Richard the Third and Carol and Glynnis the Princes. They had also pretended that he was Henry the Eighth and they were his wives. Glynnis had loved being the feisty Anne Boleyn laying her head on the chopping block. Dying could be just fine if you knew ahead of time you'd get to carry your head around in your hands and haunt people.

After dinner, Glynnis wanted to put Camper Barbie's head on the Beefeater, but it was Carol's and she wouldn't let her since it would involve cutting off Barbie's hair to make the Beefeater hat fit over top of it. They tried stuffing her hair under the hat, but it wouldn't stay on, and it looked stupid with an elastic holding it in place. And then it came to her, what she could take instead.

-Carol, Glynnis said to her class the next morning, pointing her sister out with a wave of outstretched palms like the ladies on The Price is Right showing off a fridge, -is a genetic anomaly. She is an albino.

Miss Balls

Finally to France, Beryl thought, as the crossing was under way. The sea and sky were grey, as befitted her as to war mood. She felt her eyes must be gleaming in keenness like a warrior setting out to battle.

As the ferry surged along, she had a sudden sense of the mass of things streaming into France: sheets and blankets and stretchers and ambulances, morphine and saline and ether and mortars and pestles, horses and dogs, pigeons and veterinarians, socks and scarves and sweaters and mittens, grenades, machine guns, gas masks, truckloads of bullets, boatloads of mortar shells, miles and miles of canvas, tinned food, pots and pans, evaporated milk, cigarettes, chocolate, forks, plates... But mostly them, she and Miss Boothson and Miss Flint, the troops who shared the ship, the men - mostly men, but women too - from all over the world right now steaming Franceward (and Serbiaward, and Italyward, and North Africa-ward), volunteers drawn forth from every land by the call of right action. Never before in history had there been such great traffic. And she, Beryl Balls, was a part of it, part of this great stream of human resolve. They could not fail.

Upon their arrival in Boulogne, her sense of the stream was only strengthened. The docks were lined with stores and the streets with troops: Canadians, Australians, Highlanders looking very splendid in their kilts; then, equally splendid but far more exotic, the Bengal Lancers, and not five minutes later, a company of perfectly brown Ghurkas. In turbans! Beryl felt as if their hearts were all knitting together, all the noble peoples of the Empire, uniting to defeat the foe, whether they fully understood their role or not.

They hoped for orders at their hotel, but there were none yet, and they spent the remainder of the day and most of the next exploring the old city, and this felt odd in contrast to Beryl's sense of purpose. They were like tourists with Miss Flint as chaperone and Beryl was reminded that she was to have toured the continent with her aunt and cousin in 1915. If she had to be a tourist, she was glad it was with Miss Boothson, whom she found it easier to be with than anyone she had met in her whole life. There was something about her - beyond the quick likeability that attracted everyone - that Beryl was drawn to and a little in awe of. Warmth was the chief offshoot of it, but it was not the main thing. The main thing Beryl could not for the moment identify. She only knew she would always want to be close to it.

Miss Boothson, however, did not seem to care more than was polite about Miss Balls. You could see she was one of those people who was very bright and whose intelligence made them restless. Every once in a while she condescended to join the rest of them and that warmth flashed around before shutting off again. Her great friend from Lemnos was now posted to Amiens. She remained more occupied with her letter-writing - and sketching - she dotted her letters with sketches, Beryl saw - than with anything else, though once, after tea in the hotel, she threw down her pen and said, -Oh, I hate this idleness. She stretched her hands to the ceiling, imploring, -Give us a posting. Please.

-Well, Bootsie, Miss Watson said the next morning, waving a sheet of paper at a group of them returning from a visit to local hospitals. -Your prayer's been answered.

They threw up a cheer before crowding round to see who went where.

-Flint and I for the McGill, Miss Watson said. -Ross to Le Tréport. And Bootsie and Ballsie to the No. 7 at Étaples.

Beryl flushed with pleasure.

Bootsie laughed, shaking her head. -Bootsie and Ballsie. Oh, dear.

Rowena

Rowena spotted them, the boys crouched in their box chewing wee wads of paper, phwooting them through straws. Eight year-olds playing in a dumbwaiter: an accident waiting to happen. The Smith brothers should be shot.

Quick word with the Shrinking Violet. Blithely ignore finger-pointing Pixie. Nip downstairs, catch the little beggars in the act.

-Oooowop, ooowop, went a boy's voice like a submarine siren as she pushed open the kitchen hallway's swinging doors. Sentry. How fully children participated in their escapades- it was a serious adventure indeed that needed a sentry.

-Brown cow alert, the voice added.

But gosh, there was something wrong with children these days. Honestly. The cynicism. Glynnis seemed to want to be a teenager. At seven. She looked up too much to Jay. In the kitchen, two boys hurriedly lowered the dumbwaiter, while the sentry, stood in front, arms at four and eight o'clock as if he could shield them, but he had no choice but to give way before Rowena. -I'll take over, thank you very much, she said, reaching for the ropes.

The boys tugged on the rope to lock it into place before backing off. -Hey, came a shout from the dumbwaiter, accompanied by banging on the bottom of the platform and threats to break the legs of the boys below if they left them hanging. -Leave us here and you're dead, Bialystock. D-e-d dead.

Rowena lowered, mad chatter from the box stopping before the door was even open, boys appropriately dumbstruck to open the door to Brown Owl's face instead of their friends'. With a grim sense of satisfaction, she led the bunch of them into the gym, where the rest of the cub pack gathered around Brian Smith as he and his brother demonstrated wrestling moves. No, that was being generous. They were just wrestling, the boys just watching.

In the past, Rowena had been careful to call the Smiths out into the hall to give them a piece of her mind. Children should not see their leaders called to task. Now she didn't see any reason to stand on principle.

-I'll thank you, sirs, to keep your boys in this room. They do not have the run of the church. If you cannot control them, I will ensure you lose the privilege of this hall. Brian Smith had the decency to hop up and look embarrassed. Dover just sat up on the mat. -Wo, he said. -Brown Owl, Brown Owl. Take it easy...

-I will not take it easy, this is your last warning. How many boys have to go missing before you even notice? Your whole pack could fall down the sewer. I have five boys here, five boys, gone at least ten minutes, and here the two of you are, wrestling each other like children yourselves. They could have garrotted themselves. They could have run into traffic. They could have had eight seizures.

-Yeah, but they haven't, have they? Dover Smith said.

Gah. -They were playing in the dumbwaiter. They could have killed themselves. People entrusted with the care of other peoples' children should not let them play in dumbwaiters. You are not fit to run a bath, let alone a-

But she was interrupted by a crash-brief-and a howl-long and high, just on the edge of being human.

COLLAPSEPublishers Weekly wrote:“…scenes of social trauma so pitch perfect readers will squirm in their chairs…Fleming’s ability to fully inhabit the consciousness of her characters is flawless”

“…the two central characters are exquisitely drawn”